16 Dec Echoes Of 1999: Equity Euphoria, Credit Consequences (Q3-25)

Every era of markets finds its defining narrative, and this one belongs to artificial intelligence (AI). Since the public release of ChatGPT in late 2022, AI has moved from curiosity to conviction. It is hailed as the engine of a new industrial revolution that will transform productivity, reshape industries, and redefine the relationship between capital and labor. The excitement is primarily an equity story. So far, the surge has been concentrated in valuations, venture flows, and market capitalization rather than in broad corporate borrowing. Yet that distinction is already fading. As the physical buildout of AI infrastructure accelerates, the financing of that revolution is rapidly migrating from equity to credit.

The parallels to 1999 are unmistakable. Then, the Internet promised to change the world – and it did – but not before vaporizing trillions of dollars of investor capital. The exuberance of that period was not built on ignorance but on conviction: everyone knew the Internet would matter; they simply misjudged how much, how soon, and at what cost. Today’s AI boom carries the same blend of insight and excess. The technology is real and the applications are profound, but the economics remain unproven. Faith in AI’s inevitability has replaced analysis of its profitability.

AI-related spending has become one of the principal drivers of U.S. economic resilience. According to multiple estimates, it added roughly one percentage point to U.S. GDP growth in the first half of 2025.1 In the second quarter alone, the ten largest U.S. technology firms – Alphabet, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Tesla, Apple, Nvidia, Oracle, Broadcom, and IBM – spent at an annualised rate of US$426 billion on capital investment, up 73 percent from a year earlier.2 Economy-wide technology spending as a share of GDP has now surpassed the peak seen during the late 1990s.

That surge in investment has powered not only GDP but also stock markets. Since the launch of ChatGPT, the combined market value of these ten companies has increased by nearly US$10 trillion, equivalent to roughly one-third of annual U.S. GDP. Historically, the early stages of repricing around transformative technologies are rational; capital chases genuine innovation. But enthusiasm has a way of turning to excess. Whether the current stampede will prove wise depends on the economic return on investment, a question the data have yet to answer.

The near-term math is sobering. Total revenue for the “big ten” reached about US$2.4 trillion (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the second quarter, up 15 percent from a year earlier.3 Revenue growth, however, remains well below the pace of investment, lifting the group’s capex-to-revenue ratio from 10 percent in early 2022 to roughly 18 percent today.4 Most profits still derive from established franchises—advertising for Meta, iPhone sales for Apple—rather than from AI itself. In other words, the AI story is driving valuations while legacy businesses are funding the experiment.

History also suggests that genuine productivity benefits from new technologies take longer to materialise than investors expect. While there are promising micro-level efficiencies, U.S. labour productivity has not yet broken decisively above its multi-decade trend. Despite the fanfare, the macro concern across advanced economies remains sluggish productivity growth. A recent MIT study found that 95 percent of organisations experimenting with generative AI are earning zero return on their investments.5

The problem is not intent but arithmetic. The AI buildout is exceptionally capital-intensive and depreciates at an extraordinary pace. Unlike traditional infrastructure such a poles, wires, and transmission lines that last decades, the useful life of GPUs and related processing units is measured in years, not decades. Each generation of chips is rendered obsolete by the next within three to four years, compressing the window for earning an adequate return. The physical data centres and power connections will endure; the computational core will not. As a result, the hurdle rate for profitability is far higher than most models imply. It is increasingly difficult to see how current market enthusiasm can be reconciled with the investment’s short economic life.

The AI boom’s initial financing has come largely from equity, venture capital, and retained earnings. Big Tech’s profitability and deep cash reserves gave it an extraordinary ability to self-fund early stages of the revolution. But as investment needs swell, particularly for data centres, semiconductor fabrication, and power generation, companies are turning decisively toward credit markets. Debt, not equity, will fund the next leg of AI’s expansion.

The scope has already shifted. According to Bank of America, AI-linked technology firms issued more than US$75 billion in U.S. investment-grade debt during September and October 2025 alone, more than double the sector’s average annual issuance of US$32 billion over the past decade.6 The total included US$30 billion from Meta and US$18 billion from Oracle, plus new borrowing from Alphabet and others. Barclays now identifies AI-related issuance as the key determinant of U.S. investment-grade supply in 2026,7 while J.P. Morgan estimates that AI-linked companies account for 14 percent of its investment-grade index, surpassing U.S. banks as the largest sector exposure.8

These are not speculative borrowers in the traditional sense; they are profitable, well-capitalized enterprises with legitimate business cases. Yet the sheer scale and complexity of their financing structures are giving investors pause. Meta’s US$27 billion off-balance-sheet financing with Blue Owl Capital – the largest private-credit deal ever recorded – keeps debt off Meta’s books but transfers it into opaque vehicles owned by yield-hungry investors. Such structures may provide flexibility, but they also disperse risk into corners of the market that are illiquid and difficult to price. It is this migration of leverage from transparent to opaque balance sheets that prompted the Bank of England to warn of “pockets of vulnerability” within the global financial system.9

The deeper the industry digs into infrastructure, the more circular its financing becomes. OpenAI owns a warrant to buy up to a 10 percent stake in AMD. Nvidia has invested roughly US$100 billion in OpenAI. Microsoft, OpenAI’s largest shareholder, is also one of Nvidia’s biggest customers, accounting for nearly 20 percent of its revenue, and a major client of CoreWeave, another Nvidia-backed venture. Oracle, for its part, is financing OpenAI’s US$300 billion data-centre buildout, which OpenAI will pay for using capital from investors who rely on Nvidia’s chips.

It is an ecosystem in which suppliers finance customers, competitors invest in one another, and equity stakes blur the distinction between partnership and exposure. The arrangement may be efficient in theory, but in practice it resembles the reflexive financing that defined the late-1990s telecom boom, when equipment makers lent to carriers who borrowed to buy more equipment. When funding tightened, the illusion of demand evaporated. The same pattern could repeat: when the flow of capital slows, valuations and balance sheets will adjust together.

The credit footprint of AI now extends well beyond the investment-grade market. High-yield issuance tied to AI has surged, with TeraWulf, a bitcoin miner turned data-centre operator, raising US$3.2 billion in BB-rated bonds, and CoreWeave issuing US$2 billion in high-yield debt earlier this year. These deals are small relative to the broader market, but they mark the familiar progression of optimism down the credit spectrum.

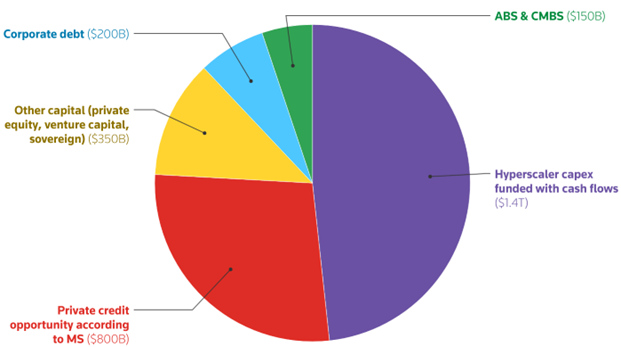

Private credit is also becoming a significant source of financing. UBS estimates that private-credit loans to AI-related borrowers nearly doubled over the twelve months through early 2025.10 Morgan Stanley projects that non-bank lenders could supply over half of the US$1.5 trillion required for the global data-centre buildout through 2028 (Figure 1).

Securitization is re-emerging as well. Digital-infrastructure asset-backed securities (ABS) – bonds backed by long-term rent payments from data-centre tenants – have expanded eightfold in five years to about US$80 billion. Bank of America expects that figure to reach US$115 billion by the end of 2026, with roughly two-thirds of issuance tied directly to data-centre construction.11 These instruments are standard financing tools, but their proliferation in a short span and their dependence on illiquid assets echo the layering that preceded the global financial crisis.

Figure 1: Morgan Stanley (MS) estimates for how the global data centre buildout will be financed (October 2025)

In this way, the logic of the cycle is self-reinforcing. Companies that spend the most on infrastructure drive the narrative that justifies further investment by others. As in past technological manias, optimism migrates from valuation to financing. The danger is not that the technology fails, but that the return profile cannot keep pace with the capital committed to it. The wisdom of this stampede will ultimately be judged by whether the economic return on investment matches its financial cost.

None of this diminishes AI’s transformative potential. Like the Internet before it, the technology will ultimately reshape how economies function and how capital is deployed. But revolutions of this scale follow a familiar pattern: optimism, overinvestment, correction, and consolidation. The productivity gains outlast the financial losses, but the investors who finance the early excess seldom own the eventual winners. Railroads in the 19th century, electricity in the early 20th, and fiber-optic networks at the turn of this century all followed this trajectory. AI will be no exception.

For credit markets, the implications are clear. As capex rises faster than cash flow, companies will lean more heavily on debt. Investment-grade issuance will expand further, private credit will deepen its exposure, and securitization will spread risk into less transparent corners of the system. The temptation for lenders will be to chase yield by funding complexity. The wiser course will be to underwrite what is real (i.e., cash-flowing, collateralised, and verifiable) rather than what is fashionable.

From a lending standpoint, AI’s credit dimension is still young but growing fast. For now, the borrowers are large, liquid, and well-rated. But as the ecosystem broadens, the risk will migrate to smaller operators and second-tier suppliers, where disclosure is weaker and covenants thinner. That is where underwriting discipline will matter most. The current environment rewards patience. We prefer to lend into dislocation, not euphoria. And to finance the infrastructure that survives the shake-out, not the speculation that precedes it.

For the moment, AI investment continues to underpin growth, earnings, and sentiment. But beneath the surface, leverage is building, complexity is rising, and transparency is declining – the same combination that has marked every great market inflection. The credit cycle is always quieter than the equity cycle until the very end. When the adjustment comes, it will not disprove the promise of AI; it will simply reprice the capital that made it possible.

[1] Macrobond, September 2025

[2] Macquarie Economics, September 24, 2025

[3] Bloomberg

[4] Macquarie Economics, September 24, 2025

[5] https://nanda.media.mit.edu/

[6] BofA Global Research, October 15, 2025

[7] Barclays Research, October 2, 2025

[8] “At $1.2 Trillion, More High-Grade Debt Now Tied to AI Than Banks,” October 7, 2025, Bloomberg

[9] “Bank of England warns of growing risk that AI bubble could burst,” October 8, 2025, The Guardian

[10] “Private Credit-Powered AI Boom at Risk of Overheating, UBS Says,” August 18, 2025, Bloomberg

[11] BofA Global Research, October 15, 2025