13 Dec Capital Crunch (Q2-22)

The sharp rise in interest rates since the start of the year has meant that all holders of fixed-rate securities, including banks, have had to write down these assets in their portfolios. The large magnitude of the write downs by banks has been exacerbated by spreads widening on credit instruments, which has reduced GAAP capital and will have implications on regulatory capital too. In fact, recent changes to regulatory capital requirements are going to dramatically impact new loan growth by banks. This is relevant to not only risk markets and the access to credit but for the ascendancy of the private debt asset class.

In Canada, regulatory capital ratios are determined in accordance with the Capital Adequacy Requirements Guideline issued by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (“OSFI”), which are based on the capital standards developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (“BCBS”). The highest quality of regulatory capital, according to the BCBS, is common equity Tier 1 capital (“CET1”) because it absorbs losses immediately when they occur. CET1 is the sum of common shares, retained earnings, other comprehensive income, qualifying minority interest and regulatory adjustments. Banks are required to maintain specified minimum levels of CET1, Tier 1 (CET1 plus other capital that is unsecured, not guaranteed, and is junior to all bank’s creditors including depositors), and total capital, determined as a percentage of risk-weighted assets.

The U.S. Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) has substantially implemented all of the BCBS’ voluntary standards (under the Basel III Accord agreed upon by members of BCBS in 2010-11) and plans to phase in final recommendations related to risk weightings beginning in January 2023. Under the Basel III rules, banks apply weights to assets based on riskiness to calculate the risk-weighted assets (“RWA”) against which they are assessed a capital charge. Government-guaranteed assets like cash, Treasuries, and certain mortgage-backed securities have a 0% risk weight and therefore there is no capital charge against them for this purpose. Most residential mortgage loans have a 50% weight (35% in Canada). Corporate loans that are unrated or rated below A- are assigned a risk weight of at least 100%.

In the U.S. and Canada, the CET1 capital requirements are made up of several components, including: (i) a minimum CET1 capital requirement of 4.5 percent of RWA; (ii) a capital conservation or stress capital buffer (“SCB”) of at least 2.5 percent; (iii) a minimum 1.0 percent surcharge for systemically important banks (“SIBs”); and (iv) a countercyclical capital buffer (“CCyB”) for SIBs that raises bank capital requirements during economic expansions as a proactive attempt to protect against insolvency in future downturns. The Fed has not used the CCyB; in Canada, OFSI administers the CCyB, called the Domestic Stability Buffer (“DSB”), which came into force in fiscal Q3-19. The DSB is reviewed by OFSI on a semi-annual basis and will range from 0-2.5% of a bank’s RWA.

During downturns, regulators would allow banks to reduce their CCyB without risking restrictive supervisory actions in order to continue to supply credit and facilitate the recovery. CCyB therefore provides surviving banks with incentives to not reduce their assets to comply with regulations and potentially worsen a downturn. For instance, in March 2020, OFSI announced lowering the DSB by 1.25 percentage points (to 0.25%), in response to challenges posed by COVID-19 and to supply additional credit to the economy. OSFI estimated at the time that the measure would support over $300 billion of additional lending capacity.

The minimum CET1 ratio in the U.S. and Canada for SIBs is currently 8.0% and 10.50%, respectively. The difference is primarily due to the Fed not requiring a CCyB.

Bank capital requirements are increasing, and this will have significant implications on credit availability. In the U.S., starting in January 2022, banks had to adopt a new approach (the Standard Approach to Counterparty Credit Risk or SACCR) to measure the counterparty risk of “off-balance sheet” derivatives. For most U.S. banks, SACCR increased the RWAs associated with derivatives contracts. In addition to the capital impairments faced from the sell-off in rates, credit spread widening, and the adoption of SAACR, U.S. banks also have to contend with annual stress capital buffer tests. The most recent results from these tests, released at the end of June 2022, point to higher required regulatory capital than expected by some of the largest banks in the country. Morgan Stanley estimates that the three largest banks (JP Morgan, Bank of America and Citigroup) alone will need to lower their RWAs by more than US$150 billion in aggregate by the end of the year if they maintain a one percentage point management buffer on top of their regulatory capital minimums. These changes affect banks’ ability to buy back stock and pay dividends but it will also undoubtedly have a bearing on capital formation, particularly in curbing riskier loans that add to RWA balances. Banks have no choice but to optimize, or as JP Morgan Chief Financial Officer Jeremy Barnum puts it, “actively manage,” their RWAs. After releasing reserves for the past six quarters, U.S. banks have built over US$1.4 billion in reserves during Q2-22.³

The situation is similar for Canadian banks, which have been building reserves in recent quarters. OFSI’s most recent semi-annual review put the DSB at 2.50%, reflecting their “assessment that key vulnerabilities remain elevated and have increased while near-term risks are moderate but rising given an environment of heightened uncertainty.” In the context of increased uncertainty, OSFI expects that “management and boards of directors exercise vigilance and heightened prudence in their capital management practices with a view to preserving capital.”⁴

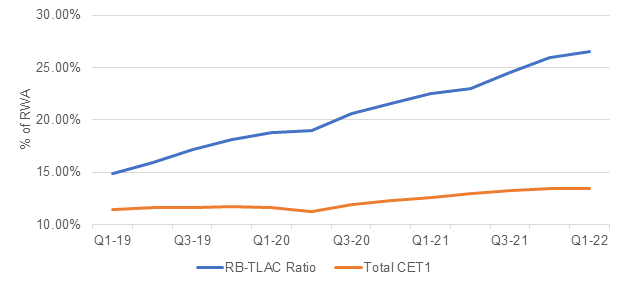

Furthermore, since SIBs are required to demonstrate a minimum capacity to absorb losses, beginning in fiscal Q1-22 (i.e., starting November 1, 2021), SIBs in Canada⁵ are expected to maintain minimum Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (“TLAC”) ratios, intended to facilitate an orderly resolution of a SIB faced with credit losses which potentially render it non-viable. The risk-based TLAC ratio (“RB-TLAC Ratio”), defined as the sum of the Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital⁶ of a SIB divided by its RWA, with the ratio expressed as a percentage, was set a minimum of 21.5% by OSFI in August 2018. The RB-TLAC Ratio has been tracked by domestic banks since fiscal Q1-2019 but did not become binding on SIBs until fiscal Q1-22.

OSFI currently expects SIBs to have a minimum RB-TLAC Ratio of 21.5% plus the DSB, for a total of 24%. As of fiscal Q1-22, the RB-TLAC Ratio for SIBs in Canada was 26.54%, the highest level for the ratio since being tracked (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Canadian SIBs Total CET1 and RB-TLAC Ratios

Source: OFSI

We believe investors have not fully appreciated the impact that new bank capital requirements will have on credit markets and the resulting boon to alternative lenders like TEC. In response to a tightening of the DSB, all types of lending conducted by Canadian banks will become more expensive. A study conducted by the Bank of Canada showed that a one percentage point tightening in CCyB decreased lending by between 12-17 percentage points.⁷ Given the higher risk weights ascribed to corporate and commercial loans, and increasing business insolvencies⁸, we expect Canadian banks’ business lending in Canada to fall. With the elevated uncertainties in the macroeconomic outlook, the descent could be dramatic. Recent commentary from banks reflects conservatism being a key issue for capital going forward. Royal Bank of Canada, the country’s largest bank, expects CET1 ratio to remain above 12.5% going forward.⁹

The biggest line in bank’s RWA is their loan portfolio, which means regulatory capital pressures will force banks to make tough choices in their lending books. The CFO of Citigroup noted on an investor conference call that the bank is requiring some of its least profitable trading clients to post more collateral and is even dropping some of them. JP Morgan indicated that it would distinguish between franchise and non-franchise lending and reduce the latter. The cost of financing is increasing not just because of higher rates but due to reduced supply. Longer term, better holders of RWAs such as business loans are firms that do not have the same regulatory capital pressures as banks. For pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and high-net worth families and individuals, the addition of loans to their portfolios is attractive and best accessed through alternative, non-bank lenders with established track records in their target markets.

[3] Credit Suisse Research, July 25, 2022

[4] OSFI Industry Letter dated June 22, 2022

[5] Six Canadian banks are designated as SIBs: Bank of Montreal, Bank of Nova Scotia, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, National Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada, and Toronto-Dominion Bank.

[6] Tier 2 capital is supplementary capital of a bank and includes expected credit loss provisions, revaluation reserves, qualifying preferred stock, subordinated term debt, hybrid instruments, and certain minority interests.

[7] Chen, David; Friedrich, Christian (2021): The countercyclical capital buffer and international bank lending: Evidence from Canada, Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper, No. 2021-61, Bank of Canada.

[8] Up 27% year over year as of May 2022 (Office of Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada).

[9] RBC company reports, June 3, 2022. CET1 ratio as at fiscal Q2-22 was 13.2%.

Article excerpted from the Q2-22 investor letter