30 Dec What Goes Up (Q4-19)

Global asset prices surged in 2019 after the dramatic “stealth QE” operations conducted by the U.S. Federal Reserve in the wholesale funding market (commonly known as the repo market). Since our Q3-2019 Investor Report, the Fed’s balance sheet has expanded by over 10% or approximately US$400 Billion! By bringing down interest rates on Treasury bills relative to bonds, the Fed essentially reversed the inverted yield curve that set self-fulfilling prophecies for a recession. The predictable result has been a continued melt up of risk assets and record debt levels. Nearly every major asset class was in the black in 2019, a sharp contrast to 2018 when fears or tightening monetary policy caused a broad-based correction in asset prices.

Investors are forced to take on more risks in a dizzying market of confusion. Bond yields are at record lows, usually a signal of impending economic stress, yet equities are at near all-time highs. Investors are unable to reach return objectives staying on the sidelines or resorting to the “safety” of bonds, and are left with no alternative but to bid-up already stretched valuations of risk assets. Studies show that banks, mutual funds, and pension funds disproportionately invest in riskier assets when interest rates are low.1 Portfolio managers, flush with liquidity, have the incentive to overinvest in risky assets, reach for yield and contribute to the formation of asset bubbles. Credit markets remain fertile ground for a bubble. The Fed’s actions have accelerated the prospects for a credit blowoff.

Must Come Down…

The S&P/LTSA US Leveraged Loan Index (the “LLI”) was up 8.64% in 2019. A great headline number that unfortunately says more about the indiscriminate speculation of investors than the fundamentals of the corporate credit markets. The share of loans in the LLI carrying a rating of single B or below increased to 50.49% in December 2019, the highest that share has ever been. Approximately US$70 Billion of leveraged loans are currently priced below 80 cents on the dollar, a common measure of distress, versus $20 Billion a year ago. The BCA Corporate Health Monitor, a composite of six key financial ratios for the non-financial corporate sector in the U.S., shows the credit quality of U.S. borrowers worsening; at the same time, return on capital for U.S. firms is rapidly falling (see Figure 1).

We painted a similar picture of the overall health of Canadian corporates in our last quarterly report. Part of the reason for worsening fundamentals among non-financial companies in Canada and the U.S. is that a lot of the debt issued post-crisis has not been for productive purposes and, therefore, has not been matched by as much asset growth as in previous cycles. In our Q3-2018 Investor Report, we posited that too many borrowings were being used for opportunistic purposes, such as dividend recapitalizations and share buybacks. Therefore, borrowings are not backed by the same extent of collateral as in the past. As we outlined in our last quarterly report, the more cushion there is to a defaulted debt instrument, the stronger the recovery. According to S&P LossStats, which tracks U.S. institutional loan recoveries, a record 35% of first-line term loans were issued in 2019 without any debt cushion; in other words, there was no layer of equity or subordination to potentially absorb losses in the event of default. As a result, the debt cushion of outstanding loans shrank to a low of 20% in 2019, versus 29% in 2009 when loan defaults peaked. When credit markets hit their tipping point of rising defaults and downgrades, recovery rates will suffer more than investors expect.

Figure 1: Deteriorating Fundamentals of U.S. Corporates, Source: BCA Research

Snap and Crackle at the Banks

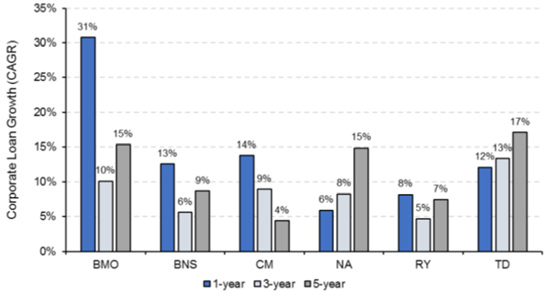

Following up on our prediction made last quarter that Canadian banks would post higher loan loss provisions in coming quarters, credit performance at the big six Canadian large cap banks was worse than expected in the fourth quarter of F2019, driven by a combination of credit losses and margin compression. Bank CEOs are finally beginning to express a more negative tone on the credit outlook and acknowledged that risks had been elevated. Total provisions for credit losses were up 31% in F2019 and reached the highest absolute ratio reported by Canadian banks since 2012 (even above 2016’s provisions caused by a downturn in the oil and gas sector). Some of this increase could be caused by scenario-driven accounting changes under IFRS 9 – seventy-three percent of the year-over-year dollar increase in loan losses came from Stage 3 provisions (loans in Stage 3 have defaulted and are non-performing); however, this still reflects guidance on weakening credit fundamentals.

The deterioration in credit is concentrated in the commercial loan book; the impaired loan ratio of consumer portfolios actually decreased for 5 of 6 of the big banks in Q4-F2019. CIBC saw the highest jump in credit loss provisions – up 53%. The bank disclosed, in an earnings call in December 2019, that it took a $52 Million provision on a syndicated loan to Eagle Travel Plaza, which operates retail gas stations, truck service centers, and fueling stations across Ontario. According to receivership filings, the borrower engaged in a large-scale fraud by concealing transactions and siphoning off cash from the business. The borrower evidently “lacked centralized record-keeping, proper controls, or a traditional governance and management structure.”2 Bank of Montreal was also affected by the fraud but has not disclosed its expected losses.

CIBC, along with Bank of Montreal, Royal Bank of Canada, and Canadian Western Bank, also announced having aggregate exposure of $200 Million to Calgary-based commercial real estate company, Strategic Group, which in December 2019 announced that was seeking credit protection under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (“CCAA”), a federal law allowing insolvent corporations that owe their creditors in excess of $5 Million to restructure their business and financial affairs. Although none of the banks involved have disclosed credit loss provisions, we believe, given the high vacancy rate for commercial properties in Alberta, that the amount and timing of recovery will be grossly overestimated.

As the current economy cycle ages, more losses can be expected on commercial loans (see below for comments on the alternative loan market). Such loans have been the fastest growing assets on bank balance sheets for the past few years, a phenomenon that has been widespread across all banks (see Figure 2). Eventually, this bubble will “pop”, credit spreads with widen, banks will tighten lending standards, and the negative knock-on effects to the economy will ultimately lead to a recession. Historically, wider credit spreads have been an excellent indicator of recessions. 3

Figure 2: Corporate Loan Growth at the Big-6 Banks, Source: National Bank Financial

Bargains in the Patch

Distressed debt investors are sitting on more than US$80 Billion and feeling pressure to invest. With very little distress in credit markets since the financial crisis, distressed debt investors are desperately waiting for the credit cycle to finally turn. We believe that a broad default wave is on the horizon but exact timing is hard to predict given accommodative monetary policy and “covenant-lite, covenant-less” loans that extend credit excesses. However, distressed lenders can find a deal-rich environment today in the oil and gas industry. Energy investments look remarkably inexpensive and have unchallenging valuations in our opinion.

Oil prices (measured by West Texas Intermediate or WTI) were up 34% in 2019 but energy producers were still the worst performer in the S&P 500. Since commodity prices bottomed in Q1-2016, oil prices have rallied 125% while the average oil stock rose by only 12%. In contrast, copper rallied 45% from its 2016 low while the average copper stock rose 130%.4

Traditional energy companies are facing a full-frontal assault from politicians, investors, and activists concerned over global warming and CO2 emissions. Capital is pouring out of investments perceived to violate environmental and sustainability concerns causing the forced liquidation of producers and service companies in the oil and gas industry. The energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables is a powerful downward force on oil and gas valuations. However, this transition is likely to take decades.

Morgan Stanley estimates that oil and gas represent 57% of the world’s primary energy mix; 86% of global energy demand still comes from fossil fuels. Wind, water, and solar account for close to 2% of the global energy mix. It took coal a half century to grow from 2% to 10%; oil and natural gas took 26 years and 33 years, respectively, to do the same. Even if oil demand peaked today, there would still be over US$40 Trillion needed, according to the International Energy Agency, for drilling, completion and field development activities before objectives under the Paris Agreement and the IEA’s own “net-zero” by 2070 target can be achieved. This means the returns on capital investment have to be attractive enough for investors, which can only occur if either oil prices rise or existing assets sell at steep discounts.

The oil and gas industry may be the only place today where lenders have the upper hand over borrowers. Investors can be extremely selective and not worry about bank or other competition driving down returns or credit protections. Existing owners, particularly private equity firms with defined exit horizons, are stranded with no liquidity. According to Reuters, an average of 67% of all oil and gas sales transactions in the last two years failed to consummate due to lack of financing. Exploration and production (“E&P”) companies are being forced to maintain capital discipline, defer non-essential capex, and maximize cash flows to investors. The CEO of one prominent, private equity-backed E&P company in Canada told us that his company had to achieve a minimum US$1 Billion in market capitalization, by consolidating or merging with competitors, before equity markets would open up liquidity options.

In the current energy environment, where oil and gas companies are forced to redefine themselves due to rapidly changing market dynamics, investors have to make their money on the buy not the sell. This means backing companies with strong competitive positions and differentiated offerings that command premium pricing. For example, as producers direct cash towards cleaning up balance sheets rather than the drill bit, drilling and completion activity will falter and oilfield service companies will struggle to stop revenues and margins from declining. As our investment in a market leading flowback production testing company proves, the most successful oilfield services companies deliver products, services, and capabilities that help operators boost productivity and reduce costs. This portfolio company enables producers to save millions in capital investment on midstream infrastructure and increase free cash flow, which makes it a critical supplier even when market sentiment is low.

Similarly, when investing in E&P companies, asset composition matters. Over the past several years, the market has generally failed to recognize any value or multiple increase for producers that own and control their own midstream and field infrastructure. We believe this is flawed because with less growth capital available to fund new infrastructure, upstream companies without owned midstream assets will become increasingly dependent on pure midstream players or, even worse, competing producers. We witnessed a similar phenomenon five years ago in the mining industry, where gold producers that owned their own processing mills could better adjust revenue mix and manage costs when commodity prices fell. Producers that own their infrastructure could position for midstream monetization events and unlock significant upside given the current valuation gap between E&P companies and the midstream sector. According to AltaCorp Capital, the multiple difference is currently approximately 7x on an enterprise value-to-cash flow basis; compared to May 2016, when intermediate upstream and midstream companies both traded at 11x cash flow. We expect the market to give credit to producers for their midstream assets as stakeholder pressure for companies to curtail spending and consolidation activity in the Canadian energy industry continues.

Our investments in the upstream oil and gas sector have always been to companies that own and control their own infrastructure. This ensures that our borrowers have uninterrupted processing capacity, can increase and diversify revenues if utilization falls, can lower operational costs, and are not beholden to third parties. It also means better exit options for us in the event of distress. The critical in-field infrastructure owned by a non-performing borrower that defaulted in 2018, for example, was a significant driver behind our successful sale of its upstream assets in 2019. Similarly, our current exposure in the CCAA restructuring of ACHL, a private, intermediate oil producer, will benefit from our collateral security and control over key processing facilities.

The restructurings affecting the oil and gas industry are ripe fruit for hungry distressed debt investors. An advantage of undergoing and emerging from a restructuring process, such as CCAA in Canada, is a clean balance sheet, a reinvigorated team, and a renewed perspective on the business This provides investors a more solid platform on which to add more reserves, either through drilling or acquisition, in order to increase scale and more easily exit.

Arif N. Bhalwani, CEO

[1] Acharya, Viral and Hassan Naqvi, 2016. On reaching for yield. Working paper. New York University Stern School of Business

[2] Receivership documents. See https://www.bdo.ca/en-ca/extranets/eagletravelplaza/

[3] BCA Research, The Bank Credit Analyst, January 2020

[4] Goehring & Rozencwajg Research